Claude Monet was born on November 14, 1840. From a young age his father wanted him to take over the family business, but Monet wanted to be an artist. In 1851, he entered the Le Havre school of arts. He was known for his charcoal caricatures. He then met an artist, Eugéne Boudin, who taught him how to use oil paints. Monet is now known for being the founder of French impressionist paintings.

Monet uses oil paints to create his pieces. Many of his works are obviously based on the impressionist style. Impressionism being an artistic style that captures the moment. Rather than achieving a depiction, it wants to reveal the emotions and experience in the moment.

This is a painting of his wife Camille. This is one of his first paintings and it is a realist painting rather than an impressionist painting. It is a life sized painting which was peculiar at that time because life sized paintings were usually contain people of royalty. He painted the background dark to emphasize Camille and what she is wearing and the details of her dress.

Monet challenged himself and created an impressionist snow scene. The name wasn’t given to the painting until five years later when it was in an exhibition. It was named after the magpie perched on the wooden gate. The painting was recognized for using such pale and gloomy colors.

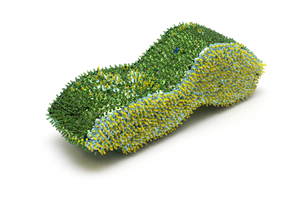

One of the paintings from the Water Lilies Series

This is one of the the paintings in his series “Nympheas”. The series consists of 250 oil paintings that he created in the last 30 years of his life. Today they are on display in Museums around the world.

This painting of the Rouen Cathedral was another series of paintings he created. In these works, he broke painting tradition and only focuses primarily in one spot. Only a portion could be seen on the canvas. Everyday he would find a new detail he hadn’t prior, so this piece was near impossible for him to create.

When he was in London, Monet painted another series based on the home of the British Parliament. There are 19 painting that are the same size of the same image. However, each image was under different weather circumstances.

This painting is another image of Camille and their eldest son. Rather than focusing on line and shape he was attentive towards light and color.

Claude Monet passed due to lung cancer on December 5, 1926. He has many of his paintings in museums all across the world. His home then now serves as an attraction for the the French Academy of fine arts in Giverny, France.

http://www.claudemonetgallery.org/biography.html

http://www.monetpaintings.org/woman-in-the-green-dress/