Learning Objectives:

- Identify the formal and iconographic characteristics of 16th-century art in Northern Europe and Spain

- Describe Dürer’s art theory and its impact on his work

- Explain how 16th-century Northern European art reflects the principles of the Protestant Reformation

- Describe how 16th-century Spanish art embodies the principles of the Catholic Counter-Reformation

- Consider how patrons employed art and architecture in the 16th century

- Explain the influence of Italian Renaissance and Mannerist art in Northern Europe and Spain

- Discuss the history, processes, and functions of prints in Northern Europe

Notes:

Glossary

predella – a step or platform on which an altar is placed.

Holy Roman Empire – A major political institution in Europe that lasted from the ninth to the nineteenth centuries. It was loosely organized and modeled somewhat on the ancient Roman Empire. It included great amounts of territory in the central and western parts of Europe. Charlemagne was its first emperor.

Protestant Reformation – The 16th-century religious, political, intellectual and cultural upheaval that splintered Catholic Europe, setting in place the structures and beliefs that would define the continent in the modern era.

Counter-Reformation – the period of Catholic resurgence initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation, beginning with the Council of Trent (1545–1563) and ending at the close of the Thirty Years’ War (1648). Initiated to preserve the power, influence and material wealth enjoyed by the Catholic Church and to present a theological and material challenge to Reformation

indulgences – a way to reduce the amount of punishment one has to undergo for sins. It may reduce the “temporal punishment for sin” after death (as opposed to the eternal punishment merited by mortal sin), in the state or process of purification called Purgatory.

genre scene – the pictorial representation in any of various media of scenes or events from everyday life, such as markets, domestic settings, interiors, parties, inn scenes, and street scenes.

still-life – a painting or drawing of an arrangement of objects, typically including fruit and flowers and objects contrasting with these in texture, such as bowls and glassware.

vanitas – a symbolic work of art showing the transience of life, the futility of pleasure, and the certainty of death, often contrasting symbols of wealth and symbols of ephemerality and death.

chiaroscuro – an effect of contrasted light and shadow created by light falling unevenly or from a particular direction on something.

contrapposto – an asymmetrical arrangement of the human figure in which the line of the arms and shoulders contrasts with while balancing those of the hips and legs.

burin – a steel tool used for engraving in copper or wood.

Iconoclasm – the social belief in the importance of the destruction of icons and other images or monuments, most frequently for religious or political reasons.

Intro

Burgundian Netherlands

- Dissolves in 1477

France and the Holy Roman Empire

- absorb these territories

- increased power

By the end of the century Spain was the dominant power.

Catholic Church is in crisis

- Reformation of the Catholic Church

- Start of Protestantism

- Church’s response, the Counter-Reformation

Reformation split Christendom in half

- Hundred years of civil war between Protestants and Catholics.

Challenges to established authority eventually led to the rise of new political and economic systems

HOLY ROMAN EMPIRE

Dissatisfaction with the Church in Rome

Martin Luther had not yet posted the Ninety-five Theses (1517)

The Catholic church in Germany still offered artists important commissions

Exchange of intellectual and artistic ideas continued to thrive

Catholic Italy and the (mostly) Protestant Holy Roman Empire traded goods and culture.

Christian Humanists

The ideas of Humanism

- started in Italy

- moved to Northern Europe

- focused on classical cultures and literature

- wanted to reconcile humanism with Christianity

- later labeled Christian Humanists

Most influential Christian humanists

- Dutch-born Desiderius Erasmus (1466–1536)

- Englishman Thomas More (1478–1535)

Erasmus

- Interest in both Italian humanism and religion with his “philosophy of Christ”

- Emphasized education and scriptural knowledge

- ordained priest and avid scholar

Published his most famous essay, The Praise of Folly, in 1509

- Satirized the Church and different social classes

Played an important role in the development of the Reformation

Declined to join any of the Reformation sects

More

- Served King Henry VIII (r. 1509–1547)

- Ordered More executed because of his opposition to England’s break with the Catholic Church

Matthias Grunewald

First View

With the exception of certain holy days, the wings of the altarpiece were kept closed, displaying The Crucifixion framed on the left by the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian pierced by arrows, and on the right by Saint Anthony the Great, remaining placid although he is being taunted by a frightening monster. The two saints protect and heal the sick, Saint Anthony as the patron saint of the victims of Saint Anthony’s fire and Saint Sebastian, whose aid was invoked to ward off the plague. Grünewald’s Crucifixion stands as one of the most poignant representations of this scene in Western art due to the artist’s masterful depiction of horrific agony, with Christ’s emaciated body writhing under the pain of the nails driven through his hands and feet. This body covered with sores and riddled with thorns must have terrified the sick, but also left no doubt about Christ’s suffering, thus comforting them in their communion with the Saviour, whose pain they shared. Mary, the mother of Jesus, is shown at Christ’s right, collapsing in anguish in the arms of John, the beloved disciple of Christ, and shrouded in a large piece of white cloth. At Christ’s left, John the Baptist is accompanied by a lamb, symbolizing the sacrifice of Jesus. The presence of John the Baptist is anachronistic. Beheaded by order of Herod in 29 AD, he could not possibly have witnessed the death of Christ. This last figure announces the New Testament by crying out, “He must increase, but I must decrease.” The inclusion of John the Baptist in this scene is symbolic, since he is considered as the last of the prophets to announce the coming of the Messiah.

Second View

The outer wings of the Isenheim Altarpiece were opened for important festivals of the liturgical year, particular those in honour of the Virgin Mary. Thus are revealed four scenes: the left wing represents the Annunciation during which the archangel Gabriel comes to announce to Mary that she will give birth to Jesus, the son of God. The Virgin Mary is depicted in a chapel to indicate the sacred character of the event. In the central corpus, the Concert of Angels and the Nativity are not independent scenes but instead fit within a unified concept: the viewer witnesses Christ’s coming to earth as a newborn baby, who will be led to combat the forces of evil personified by certain of the angels, disturbing in their physical appearance. A number of symbols provide keys to aid in interpretation: the enclosed garden represents Mary’s womb and is a sign of her perpetual virginity, the rose bush without thorns refers to her as free of original sin, the fig tree symbolises mother’s milk. The bed, the bucket and the chamber pot underscore the human nature of Christ. Lastly, the right wing shows the Resurrection, in which Christ emerges from the tomb and ascends into Heaven bathed in light transfiguring the countenance of the Crucified into the face of God. The Resurrection and the Ascension are therefore encapsulated in a single image.

Third View

Saint Augustine and Guy Guers, Saint Anthony, Two Bearers of Offerings, Saint Jerome, Christ and the Twelve Apostles With its inner wings open, the Altarpiece allowed pilgrims and the afflicted to venerate Saint Anthony, protector and healer of Saint Anthony’s fire. Saint Anthony occupies the place of honour at the centre of the corpus and at his side a pig is depicted, the emblem of the Antonite order. On his left and right, two bearers of offerings illustrate these contributions in kind, an important source of income for the Antonites. This central section is framed by Saint Augustine and Saint Jerome, two of the four great fathers of the Latin Church. Guy Guyers, who had commissioned the Altarpiece, is depicted kneeling at the feet of Saint Augustine.

Visit of Saint Anthony to Saint Paul the Hermit The two hermits meet in a stunning landscape, intended to represent the Theban Desert. Grünewald created a fantastic universe, surrounding the date palm with a strange mixture of vegetation, in marked contrast with the calmness and tranquillity of the encounter, in which the animals in attendance take part, with the crow bringing two morsels of bread to the two recluses. In this dreamlike scene, medicinal plants, painted in naturalistic fashion, sprout at the feet of the two main figures.

Saint Anthony Tormented by Demons This panel depicts Saint Anthony being tormented by monstrous creatures sent by Satan. Trampled to the ground, beaten with sticks, torn by claws and bitten, Saint Anthony appeals to God for help who sends angels to combat these evil demons. In the lower left corner, the being with webbed feet and a distended belly seems to personify the disease caused by ergot poisoning, resulting in swelling and ulcerous growths.

Hans Baldung Grien

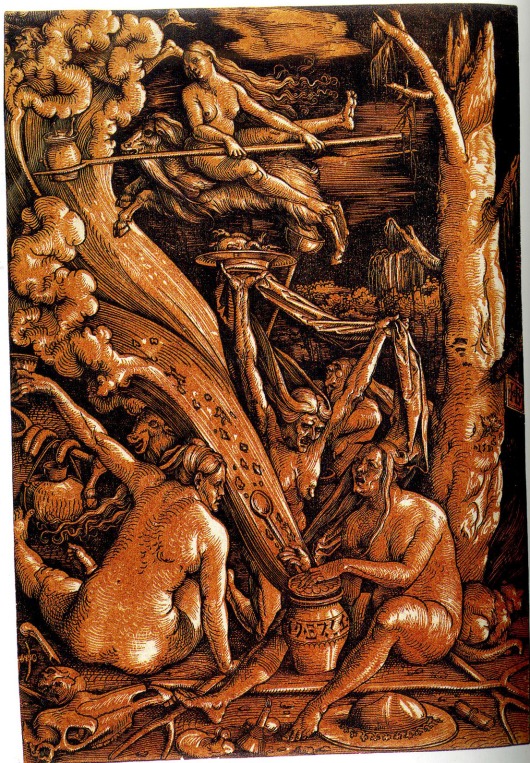

HANS BALDUNG GRIEN, Witches’ Sabbath, 1510. Chiaroscuro woodcut, 1’ 2 7/8” X 10 ¼”. British Museum, London.

Witches’ Sabbath by Hans Baldung Grien

- produced in 1510

- Chiaroscuro woodcut

Chiaroscuro woodcuts were a recent German innovation

- Uses two blocks

- Printmaker carves and inks one block to make a black-and-white print

- Artist cuts a second block that can be inked in gray or color (printed over the first block’s impression)

The more shading or value a work of art has, the more three dimensional it appears

Witchcraft

- counter-religion in the 15th and 16th centuries

- involved magical rituals, secret potions, and devil worship

- Witches prepared brews that they inhaled or rubbed into their skin

- Hallucinogene trances

- Allegedly flew through the night sky on broomsticks or goats

Popes condemned all witches

- Inquisitions pursued the witches

- Subjected them to torture to get confessions from them

Several inquisitions to “weed” out the witches.

- the Medieval Inquisition (1231–16th century)

- the Spanish Inquisition (1478–1834)

- the Portuguese Inquisition (1536–1821)

- the Roman Inquisition (1542 – c. 1860)

Witchcraft fascinated Baldung

- For him witches were evil forces in the world

- Baldung often illustrated Eve as a temptress responsible for Original Sin

In Witches’ Sabbath

- Baldung depicted a night scene in a forest

- coven of nude witches

- Both young seductresses and old witches gather around a covered jar

- One young witch rides through the night sky on a goat

- She sits backward – suggesting its the opposite of the true religion, Christianity

Hans Baldung (1485-1545) had a personal fascination with magic and the supernatural, as is clear from his many woodcuts. He came from a professional Strasbourg family, but worked from 1503 to 1507 in Dürer’s workshop in Nuremberg. In 1510 another Strasbourg artist, Hans Wechtlin, employed the new technique of colour woodcut to suggest light and shade. Baldung however has used his tone block to establish the mood of his sinister subject, which he could vary from impression to impression by changing the ink colour, or by printing from the black line block alone.

Baldung’s obsession with magic and witchcraft gave vivid expression to the fears of religious heresy, social dissolution, and hidden female powers that preyed on the late medieval imagination. The woodcut was published in Strasbourg, whose bishop had been made executor of a papal bull against witchcraft in 1484. Three years later, the Malleus Maleficarum, a terrible handbook for rooting out witchcraft, was also published in Strasbourg, and ran to many editions.

The signed and dated print shows four naked women surrounded by the paraphernalia of their black art. To the shrieking incantation of an old woman, her young companion lifts the lid off a pot from which fumes and unspeakable ingredients sweep high into the night air. A fifth woman rides backwards through the sky on a goat.

Albrecht Durer

ALBRECHT DÜRER, Self-Portrait, 1500. Oil on wood, 2’ 2 1/4” X 1’ 7 1/4”. Alte Pinakothek, Munich.

Albrecht Durer

Travelled through Europe and became an international celebrity

Took trips to Italy to study Renaissance art

First artist to blend Northern European stylistic features (detail, realistic rendering of objects, symbols hidden as everyday objects) with Italian features (classical body types, linear perspective). Durer greatly admired the work of Leonardo. He was also was one the first artists to keep a thorough record of his life through self-portraits and a diary.

Important graphic artist — best known for his engravings

Influenced significantly by Martin Luther and Protestant Reformation

A supremely gifted and versatile German artist of the Renaissance period, Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) was born in the Franconian city of Nuremberg, one of the strongest artistic and commercial centers in Europe during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. He was a brilliant painter, draftsman, and writer, though his first and probably greatest artistic impact was in the medium of printmaking.

Dürer apprenticed with his father, who was a goldsmith, and with the local painter Michael Wolgemut, whose workshop produced woodcut illustrations for major books and publications. An admirer of his compatriot Martin Schongauer, Dürer revolutionized printmaking, elevating it to the level of an independent art form. He expanded its tonal and dramatic range, and provided the imagery with a new conceptual foundation. By the age of thirty, Dürer had completed or begun three of his most famous series of woodcuts on religious subjects: The Apocalypse (1498), the Large Woodcut Passion cycle (ca. 1497–1500), and the Life of the Virgin (begun 1500). He went on to produce independent prints, such as the engraving Adam and Eve, and small, self-contained groups of images, such as the so-called Master Engravings featuring Knight, Death, and the Devil, Saint Jerome in His Study (1514), and Melancholia I, which were intended more for connoisseurs and collectors than for popular devotion. Their technical virtuosity, intellectual scope, and psychological depth were unmatched by earlier printed work.

More than any other Northern European artist, Dürer was engaged by the artistic practices and theoretical interests of Italy. He visited the country twice, from 1494 to 1495 and again from 1505 to 1507, absorbing firsthand some of the great works of the Italian Renaissance, as well as the classical heritage and theoretical writings of the region. The influence of Venetian color and design can be seen in the Feast of the Rose Garlands altarpiece (1506; Prague, Národní Galerie), commissioned from Dürer by a German colony of merchants living in Venice.

Dürer developed a new interest in the human form, as demonstrated by his nude and antique studies. Italian theoretical pursuits also resonated deeply with the artist. He wrote Four Books of Human Proportion (Vier Bücher von menschlichen Proportion), only the first of which was published during his lifetime (1528), as well as an introductory manual of geometric theory for students, which includes the first scientific treatment of perspective by a Northern European artist.Dürer’s talent, ambition, and sharp, wide-ranging intellect earned him the attention and friendship of some of the most prominent figures in German society.

He became official court artist to Holy Roman EmperorsMaximilian I and his successor Charles V, for whom Dürer designed and helped execute a range of artistic projects. In Nuremberg, a vibrant center of humanism and one of the first to officially embrace the principles of the Reformation, Dürer had access to some of Europe’s outstanding theologians and scholars, including Erasmus, Philipp Melanchthon, and Willibald Pirkheimer, each captured by the artist in shrewd portraits. For Nuremberg’s town hall, the artist painted two panels of the Four Apostles (1526), bearing texts in Martin Luther’s translation that pay tribute to the city’s adoption of Lutheranism.

Hundreds of surviving drawings, letters, and diary entries document Dürer’s travels through Italy and the Netherlands (1520–21), attesting to his insistently scientific perspective and demanding artistic judgment.The artist also cast a bold light on his own image through a number of striking self-portraits—drawn, painted, and printed. They reveal an increasingly successful and self-assured master, eager to assert his creative genius and inherent nobility, while still marked by a clear-eyed, often foreboding outlook. They provide us with the cumulative portrait of an extraordinary Northern European artist whose epitaph proclaimed: “Whatever was mortal in Albrecht Dürer lies beneath this mound.”

Albrecht Durer's The Fall of Man

ALBRECHT DÜRER, The Fall of Man (Adam and Eve), 1504. Engraving, 9 7/8” x 7 5/8”. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (centennial gift of Landon T. Clay).

The Fall of Man by Albrecht Durer

- Known more as a printmaker than as a painter

- Trained as a goldsmith by his father before he took up painting and printmaking

Created numerous book illustrations

- Sold prints in single sheets, made available to the masses

- became wealthy from the sale of these works

His wife, was his manager while his mother sold his prints at markets. He had a very strong influence in both Flanders and Italy

Fall of Man

- One of Dürer’s early masterpieces

- First use of the theory of human proportions, a theory based on arithmetic ratios

Outlined against the dark background of a northern forest

- idealized figures of Adam and Eve

- look like classical statues

- concept of the “perfect” male and female figures.

- detail in the background and animals

- bark of the trees

- leaves authenticate the scene

- creatures behind them

Animals represent the 4 humors of Hippocratic medicine

- black bile – the elk

- yellow bile – the cat

- phlegm – the ox

- blood – the rabbit

The cat and mouse symbolizes the relationship between Adam and Eve

Under the influence of Italian theory, Dürer became increasingly drawn to the idea that the perfect human form corresponded to a system of proportion and measurements. Near the end of his life, he wrote several books codifying his theories: the Underweysung der Messung (Manual of measurement), published in 1525, and Vier Bücher von menschlichen Proportion (Four books of human proportion), published in 1528, just after his death. Dürer’s fascination with ideal form is manifest in Adam and Eve. The first man and woman are shown in nearly symmetrical idealized poses: each with the weight on one leg, the other leg bent, and each with one arm angled slightly upward from the elbow and somewhat away from the body. The figure of Adam is reminiscent of the Hellenistic Apollo Belvedere, excavated in Italy late in the fifteenth century. The first engravings of the sculpture were not made until well after 1504, but Dürer must have seen a drawing of it. Dürer was a complete master of engraving by 1504: human and snake skin, animal fur, and tree bark and leaves are rendered distinctively. The branch Adam holds is of the mountain ash, the Tree of Life, while the fig, of which Eve has broken off a branch, is the forbidden Tree of Knowledge. Four of the animals represent the medieval idea of the four temperaments: the cat is choleric, the rabbit sanguine, the ox phlegmatic, and the elk melancholic. Before the Fall, these humors were held in check, controlled by the innocence of man; once Adam and Eve ate from the apple of knowledge, all four were activated, all innocence lost.

Albrecht Durer's Turf

ALBRECHT DÜRER, Great Piece of Turf, 1503. Watercolor, 1’ 3/4” x 1’ 3/8”. Albertina, Vienna.

GREAT PIECE OF TURF

Painted a very precise watercolor study of a piece of grass

- Observation yielded truth.

- Dürer agreed with Aristotle (and Leonardo) that “sight is the noblest sense of man.”

“Nature holds the beautiful, it is the artist who has the insight to extract it.” Beauty even exists in just grass

Very accurate painting

- each plant can be identified

The Great Piece of Turf is a watercolor painting by Albrecht Dürer. The painting was created at Dürer’s workshop in Nuremberg in 1503. It is a study of a seemingly random group of wild plants, including dandelion and greater plantain. The work is considered one of the masterpieces of Dürer’s realistic nature studies.

The watercolour shows a large piece of turf and little else. The various growths can be identified as cock’s-foot, creeping bent, smooth meadow-grass, daisy,dandelion, germander speedwell, greater plantain, hound’s-tongue and yarrow.

The painting shows a great level of realism in its portrayal of natural objects. Some of the roots have been stripped of earth to be displayed clearly to the spectator. The depiction of roots is something that can also be found in other of Dürer’s works, such as Knight, Death, and the Devil (1513).The vegetation comes to an end on the right side of the panel, while on the left it seems to continue on indefinitely. The background is left blank, and on the right can even be seen a clear line where the vegetation ends.

Albrecht Durer's Knight, Death and the Devil

ALBRECHT DÜRER, Knight, Death, and the Devil, 1513. Engraving, 9 5/8” x 7 3/8”. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

KNIGHT, DEATH, AND THE DEVIL

Interest in both idealization and naturalism

- Engraving

- texture and tonal values

Mounted armored knight

- rides through a landscape of death

- the knight represents a Christian knight—a soldier of God

- Armed with his faith, this warrior can repel the threats of Death

- Death appears as a dead king covered with snakes

- Shakes an hourglass as a reminder of time and mortality

- The Devil follows the Knight, but he pays him no attention

Copied a number of Leonardo’s sketches of horses

Engraving

Engraving is done with a very sharp tool called a burin. The burin is held in the palm of the hand and pushed through the copper engraving plate. As the burin moves through the plate it removes a small amount of copper that twists away like an apple paring. Engraved lines display several idiosyncrasies that help distinguish them from etched or drypoint lines. First of all the lines are almost inevitably elegant, gently arcing strokes that start as a point, swell to a larger width, and taper off again. The width of the line can be modulated by pressure or by repeated engraving. The burin also lends itself to little flicks and stabs that have a characteristic triangular shape (see knight’s helmet for a good example). Dürer developed a sophisticated system that uses engraved lines almost like the lines of a topological map to describe forms (notice the way the lines in the horse’s neck define the shape of the neck as well as its tonality). The logical conclusion of this technique is the tight vocabulary of reproductive engraving. Dürer engraved passages that resemble a staggering array of textures and surfaces (compare, for example, the hair of the dog, the surface of the armor and the leather of the knight’s boot.

Dürer’s Knight, Death, and the Devil is one of three large prints of 1513–14 known as his Meisterstiche (master engravings). The other two are Melancholia I and Saint Jerome in His Study. Though not a trilogy in the strict sense, the prints are closely interrelated and complementary, corresponding to the three kinds of virtue in medieval scholasticism—theological, intellectual, and moral. Called simply the Reuter (Rider) by Dürer, Knight, Death, and the Devil embodies the state of moral virtue. The artist may have based his depiction of the “Christian Knight” on an address from Erasmus’s Instructions for the Christian Soldier (Enchiridion militis Christiani), published in 1504: “In order that you may not be deterred from the path of virtue because it seems rough and dreary … and because you must constantly fight three unfair enemies—the flesh, the devil, and the world—this third rule shall be proposed to you: all of those spooks and phantoms which come upon you as if you were in the very gorges of Hades must be deemed for naught after the example of Virgil’s Aeneas … Look not behind thee.” Riding steadfastly through a dark Nordic gorge, Dürer’s knight rides past Death on a Pale Horse, who holds out an hourglass as a reminder of life’s brevity, and is followed closely behind by a pig-snouted Devil. As the embodiment of moral virtue, the rider—modeled on the tradition of heroic equestrian portraits with which Dürer was familiar from Italy—is undistracted and true to his mission. A haunting expression of the vita activa, or active life, the print is a testament to the way in which Dürer’s thought and technique coalesced brilliantly in the “master engravings.”

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation

Growing dissatisfaction with Church leadership.

Roman popes concerned themselves more with power and wealth than with the salvation of Church members

- Many 15th-century popes and cardinals came from wealthy families

Upper-level clergy (such as archbishops, bishops, and abbots) began to accumulate numerous positions

- Increasing their revenues

- Could not fulfill all of their responsibilities

By 1517 dissatisfaction with the Church had grown wide-spread

- Luther felt free to challenge the pope’s authority publicly

- Ninety-five Theses

- Objections to Church practices, especially the sale of indulgences.

Indulgences were Church-sanctioned remittances (or reductions) of time spent in Purgatory

- People were essentially buying their way into Heaven

Luther’s goal was significant reform and clarification of major spiritual issues

- Ultimately led to the splitting of Christendom

According to Luther

- the Catholic Church’s religious and political structure needed to be cast out

- had no basis in scripture.

- Only the Bible—nothing else—could serve as the foundation for Christianity

Luther declared the pope the Antichrist

- Pope excommunicated him

- called the Church the “whore of Babylon”

- denounced ordained priests

- Rejected most of Catholicism’s sacraments

- said they were pagan obstacles to salvation

Luther said that for Christianity to be restored to its original purity, the Church must be cleansed of all the doctrinal impurities that had collected through the ages. Said the Bible as the source of all religious truth. The Bible—the sole scriptural authority—was the word of God. Luther helped make the first translation of the Bible in a vernacular (language of the people) language

The Protestant Reformation

At this point in history there is only one church in the West — the Catholic Church — under the leadership of the Pope in Rome. The Church had been for some time a notoriously corrupt institution plagued by internal power struggles (at one point in the late 1300s and 1400s there was a power struggle within the church resulting in not one, but three Popes!), and Popes and Cardinals often lived more like Kings or Emperors than spiritual leaders. Popes claimed temporal (or political) power as well as spiritual power, commanded armies, made political alliances and enemies, and waged war. Simony (the selling of church offices) and nepotism (favoritism based on family relationships) were rampant. Clearly, if the Pope was concentrating on these worldly issues, there wasn’t much time left for caring for the souls of the faithful! The corruption of the Church was well known, and several attempts had been made to reform the Church, but none of them was successful until Martin Luther in the early 1500s.Martin Luther, a German priest, began the Protestant Reformation (before we go on, notice that Protestant contains the word “protest” and that reformation contains the word “reform” — this was an effort, at least at first, to protest against some of the practices of the Catholic Church and to reform the Church). Luther began the Reformation in 1517 by posting his “95 Theses” on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany –these theses were a list of statements that expressed Luther’s concerns about some Church practices. Luther had four main gripes with the church that I would like to discuss: 1. Good Works 2. Transubstantiation 3. The Sale of Indulgences 4. The Role of art in the church

1. Good Works

Luther, a very devout man, had experienced a spiritual crisis. Luther recognized that no matter how “good” he tried to be, no matter how he tried to stay away from sin, he still found himself having sinful thoughts. He was fearful that no matter how many good works he did, he could never do enough to earn his place in heaven (remember that, according to the Catholic Church, doing good works, like commissioning works of art for the Church helps one’s chances of getting to heaven). I think that this was a profound recognition of the inescapable sinfulness of the human condition. After all, no matter how kind and good we try to be, we all find ourselves having thoughts which are unkind and sometimes much worse. And I’m not talking here about serious sinful thoughts, but also more minor thoughts: for example, haven’t you ever been jealous of a friend’s success, and then in your heart found yourself happy when something went wrong for them? Luther found a way out of this problem by reading St. Paul, who wrote “The just shall live by faith alone.” Translated into 21st century English that means that those who go to heaven (the just) will get there by faith alone — not by doing good works! In other words, according to Luther you cannot earn yourself a place in heaven.

2. Transubstantiation

Transubstantiation is the miracle whereby, during Holy Communion, when the priest administers the bread and wine, they change (the prefix “trans” means to change) their substance into the body and blood of Christ. Luther said that the priests — and even the Pope — had no special power to make that change happen. He said the priests and the Pope have no closer relationship to God than anyone else, and he denied that anything changed substance during Holy Communion. Luther says that if you go back and read the bible it says nothing about bread and wine changing their substance into the body and blood of Christ by the power of a priest — therefore do not listen to the teachings of the church, and read the Bible for yourself (see below for how this was now possible)! Luther thereby challenged one of the central sacraments of the Catholic Church, one of its central miracles, and thereby one of the ways that human beings can achieve grace with God, or salvation. Luther essentially says that people should not listen to what the Church tells them — because the church misleads them about the true teachings of Christ, they should read the bible for themselves — and, lo and behold, this is when the printing press was invented! So one of the first things Luther does is translate the bible into German– soon after, it got printed and for the first time in history people could read the bible for themselves! Before this all bibles were copied by hand.

3. The Sale of Indulgences

Luther attacked one of the most obvious abuses of the time — the sale of indulgences by the Church. This was a practice where the church sold you a piece of paper that bought you time off from purgatory. Purgatory is a place between heaven and hell, where souls who need to do more repenting go before they go to heaven. This meant that people who were wealthy — who could purchase an indulgence, spent less time in purgatory than poor people — exactly the opposite of Christ’s teachings where he says that it is easier for a poor man to get to heaven than for a rich man.

4. The role of art in the church

Luther and his followers agreed that there should be no art in the church for two reasons: 1. It cost large amounts of money money that would be better spent on feeding the poor. 2. It is too close to a violation of one of the ten commandments which forbids the making of any idol or image of God. As a result, in areas of Europe that converted to Protestantism artists can no longer work for their most important patron — the church! We’ll look at Protestant Holland to see what happens to artists there.

The Counter-Reformation

At first, the Church ignored Martin Luther, thinking that he would just go away. When that didn’t work, they excommunicated him (in other words they kicked him out of the church so that, according to them, he could never go to heaven). Luther’s ideas (and variations of them, including Calvinism and Anglicanism) quickly spread throughout Europe. As we have seen, there were many reasons for opposing the Church during this period. The Church’s response to the threat from Luther and others during this period is called the Counter-Reformation (“counter” meaning against).

In 1545 the Church called the Council of Trent to deal with the issues raised by Luther. The Council of Trent was an assembly of high officials in the Church who met (on and off for eighteen years) in the Northern Italian town of Trent for 25 sessions.

These are some of the outcomes of the Council:

1. The Council agreed that the Church was corrupt and needed reform in several areas. They prohibited any further sale of indulgences and simony was disallowed.

2. The Council denied the Lutheran idea of justification by faith. They affirmed, in other words, their Doctrine of Merit, which allows human beings to redeem themselves through Good Works, and through the sacraments.

3. They affirmed the existence of Purgatory and the usefulness of prayer and indulgences in shortening a person’s stay in purgatory.

4. They reaffirmed the belief in transubstantiation

5. They reaffirmed the necessity and correctness of religious art

So, at the Council of Trent, the Church reaffirms the usefulness of images — but is careful not to violate the commandment against creating graven images. They are careful, in other words, to try to prevent people from worshipping the images themselves. But the images are important “because the honour which is shown them is referred to the prototypes which those images represent” and “because the miracles which God has performed by means of the saints, and their salutary examples, are set before the eyes of the faithful; that so they may give God thanks for those things; may order their own lives and manners in imitation of the saints; and may be excited to adore and love God, and to cultivate piety.”

Cranach's Allegory of Law and Grace

LUCAS CRANACH THE ELDER, Allegory of Law and Grace, ca. 1530. Woodcut, 10 5/8” x 1’ 3/4”. British Museum, London.

Catholic and Protestant views of salvation

- Luther said that people cannot earn salvation, it is through faith and grace alone

- No priest nor indulgence could save sinners face-to-face with God

- Only faith in God could save you

In Allegory of Law and Grace

Lucas Cranach the Elder is used to show the differences between Protestantism and Catholicism. Cranach was a follower and close friend of Martin Luther. (They were godfathers to each other’s children.) Cranach produced his woodcut about 12 years after Luther’s Ninety-five Theses.

Two images separated by a tree

- Catholicism (based on Old Testament law, according to Luther)

- Protestantism (based on a belief in God’s grace)

On the left side

- Judgment Day

- Christ is at the top, surrounded by angels and saints.

- He raises his left hand, which meant damnation

- A skeleton pushes a person towards Hell.

- This person tried to live a good and honorable life but fell short.

- Moses stands to the side, holding the Tablets of the Law

- —the commandments Catholics follow in their attempt to attain salvation.

On the right side

- Protestants emphasized God’s grace as the source of redemption.

- God showers the sinner in the right half of the print with grace

- Streams of blood flow from the crucified Christ.

- Christ emerges from the tomb

The most effective and successful of the doctrinal representations came from the school of Lucas Cranach, the contrast between the Law and the Gospel, or the Old and New Testaments. The earliest example from Lucas Cranach the Elder comes from the later 1520s. It is based on the antithesis, a form used so often throughout Reformation propaganda. The visual space is divided down the centre by a tree, to the left of which is depicted the Law as expounded in the Old Testament. In the left background, Adam and Eve east the fruit of the tree of life after being tempted by the serpent. As a result of this original sin, man is the prey of death and the Devil, through he can only be damned, indicated by the two figures hounding Man into the jaws of hell. This is Man under the Law, signified by Moses holding the tables of the Ten Commandments, with other Old Testament prophets behind him. In the clouds above, Christ as Lord of the world sits judging man, with the sword and the lily in his ears. Two figures, Mary and John the Baptist, seek to intercede for sinful man, although in vain. The gloomy message of the Old Testament and the Law, which only condemn man, is also signified in the barren branches on the Old Testament side of the antithesis formed by the central tree.

In opposition to the hardness of the Law, the Gospel brings hope, signified by the blooming branches on the New Testament side of the tree. In the background is depicted, however, an Old Testament scene, the brazen serpent, the figure of Christ’s saving death on the cross. On the hill in the right background Mary receives the rays of heavenly grace, signifying the incarnation, further indicated by the angel bearing the cross down to her. To the left, further indicated by the angel brings the news of the birth of the Savior to the shepherds on the hills of Bethlehem. The main figures on this side depict the events through which the Gospel message is realized. The crucified Christ sheds his saving blood in a stream onto man. Through the agency of the Holy Spirit, the dove through which the stream passes, this becomes the saving water of baptism. Man has his attention called to the sacrificial death of Christ by the figure of John the Baptist. Beneath the crucifix is the paschal lamb, the symbol of Christ’s victorious death, which is completed by his resurrection. This is depicted in the bottom right-hand corner, where Christ overcomes death and the apocalyptic beast, representing the Devil. This completes man’s release from sin and death, neatly balancing the corresponding depiction on the far left.

This schema became one of the most popular themes of the Reformation, largely because it captured so effectively the gist of Luther’s doctrine. Indeed, it seems to have been most directly inspired by some of Luther’s expositions on the theme of the Law and the Gospel, such as that in his commentary on Galatians. It was a wholly biblical depiction and relied on signs accessible to every person of the time. Above all, it established a uniquely evangelical position, without reference to papal or Catholic teaching. It could be used purely as a visual representation, or supplied with appropriate biblical references…. The Law is headed by a citation from Romans 1.18: “The wrath of God is revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and wickedness of men.” The Gospel is headed by a verse of Isaiah 7.14, which shows the prophetic link between the Old and New Testaments: “The Lord himself will give you a sign. Behold, a young woman shall conceive and bear a son.” Beneath the depiction of the Law are quotations spelling out its significance ( Romans 3.23; 1 Corinthians 5.56; Romans4.15; Romans 3.20 and Matthew 11.13). The Gospel is likewise supplied with texts on faith (Romans 1.17 and 3.21 –both classic expressions of the basic Lutheran doctrine that the just live through faith), and expressing the hope of salvation (John 1.29; 1 Peter 1.2 and 1 Corinthians 15.55). The combination of scriptural texts and visual signs expressing their content made such a depiction the evangelical version of the Pauper’s Bible.

Holbein's The French Ambassodors

HANS HOLBEIN THE YOUNGER, The French Ambassadors, 1533. Oil and tempera on wood, approx. 6’ 8” x 6’ 9 1/2”. National Gallery, London.

The French Ambassadors by HANS HOLBEIN

Portrait pianter

- Trained by his father

- made portraits of incredible realism

- Popular in Flemish art

- Italian ideas about monumental composition and sculptural form.

Double portrait of the French ambassadors to England, Jean de Dinteville (at left) and Georges de Selve.

- Strong sense of composition.

The two men

- Both humanists

- stand at opposite ends of a side table covered with an oriental rug and a collection of objects

- Objects symbolize their worldliness and their interest in learning and the arts.

- Includes mathematical and astronomical models

- A lute with a broken string

- compasses

- sundial

- flutes

- globes

- an open hymnbook with Luther’s writings and the Ten Commandments.

Long gray shape across the bottom

- anamorphic image.

- A distorted image recognizable only when viewed with a special device, like a round mirror, or by looking at the painting at a strong angle.

- If the viewer stands off to the right, the gray slash becomes a skull.

- Put your face to the left of your computer screen. You should see the skull in the center of the painting.

Reference to death

- common in paintings as reminders of mortality.

May allude to tension between the secular and religious.

Francis I

FRANCE

France in the early 16th century was a dominant political power and cultural force. The French kings were major patrons of art and architecture.

JEAN CLOUET, Francis I, ca. 1525–1530. Tempera and oil on wood, approx. 3’ 2” x 2’ 5”. Louvre, Paris.

Under Francis I

- French established its power in Milan.

- waged war against Charles V (the Spanish king and Holy Roman Emperor), from 1521 to 1544.

- wars involved disputed territories

- southern France, the Netherlands, the Rhinelands, northern Spain, and Italy.

Took a strong position in the religious controversies of his day.

- Catholics and Protestants were now very distinct

- France was predominantly Catholic

- in 1534, Francis declared Protestantism illegal.

- The state persecuted its Protestants, the Huguenots, and drove them underground.

- Huguenots’ commitment to Protestantism led to one of the bloodiest religious massacres in European history

- Protestants and Catholics fought in Paris on August 24, 1572

Francis I

- wanted to make his country have more culture.

- invited several popular Italian artists, including Leonardo da Vinci, to Milan.

The King, not the Christian Church, holds power

- Needs new works of art that reflect the monarchy and not religion

Artist Jean Clouet

- Painted portrait of Francis I about a decade after he became king

- dressed in silks

- wearing a gold chain with a medallion

- apparently was a great lover

- hundreds of “heroic” deeds.

- appears confident

- hand on a dagger.

- flattens features (neck)

- Favored art that was elegant, erotic, and different.

Mannerism appealed to them

Architecture

Château de Chambord, Chambord, France, begun 1519.

Francis I

- commissioned several large châteaux

- served as country houses for royalty

- usually built near forests for use as hunting lodges.

Construction of Chambord began in 1519

- Francis I never saw it finished.

- central square block with four corridors

- in the shape of a cross

- broad, central staircase that gives access to groups of rooms

- like modern day apartments.

- moat surrounds the whole.

- three levels, molding separates the floors.

- Windows align precisely, one exactly over another.

- The Italian Renaissance palazzo served as the model

Louvre, Paris

Francis I initiated the project to update and expand the royal palace

- Died before the work was well under way

Pierre Lescot (1510–1578)

- Architect of Francis I

- Continued under Henry II

- Produced the classical style later associated with 16th-century French architecture

Built during the reign of Francis’s successor, Henry II (r. 1547–1559)

- Italian architects came to work in France

- French went to Italy to study and travel

- Caused a revolution in style than earlier

Louvre in Paris

- Incorporation of Italian architectural ideas

- Originally a medieval palace and fortress

Charles V’s renovated the Louvre in the mid-14th century

- had started to fall apart

PIERRE LESCOT, west wing of the Cour Carre (Square Court) of the Louvre, Paris, France, begun 1546.

In the west wing of the Cour Carré of the Louvre

- Each of the stories forms a complete order (doric, ionic, corinthian)

- horizontal bands.

The arcading on the ground story reflects the ancient Roman use of arches

- Produces more shadow than in the upper stories due to its recessed placement

- Strengthening the design’s base

On the second story

- Pilasters rising from bases &

- Alternating curved and angular pediments

Northern and French Features vs Italian Features

- The decreasing height of the stories

- The scale of the windows (proportionately much larger than in Italian Renaissance buildings)

- Steep Roof

- double columns framing a niche

- tall and wide windows

- profuse statuary

Art in the Netherlands in the 16th Century

THE NETHERLANDS

Netherlands at the beginning of the 16th century consisted of 17 provinces (corresponding to modern Holland, Belgium, and Luxembourg).

Most prosperous European countries.

Extensive network of rivers

- Easy access to the Atlantic Ocean

- Lots of overseas trade

- Shipbuilding was one of the most profitable businesses.

Traffic relocated to Antwerp

- became the hub of economic activity in the Netherlands after 1510.

- 500 ships a day passed through Antwerp’s harbor

- large trading companies from England, the Holy Roman Empire, Italy, Portugal, and Spain established themselves in the city.

Second half of the 16th century

- Netherlands under control of Philip II of Spain.

- Wanted to tighten control over the area.

- Aggressive tactics led to a revolt in 1579

- formation of two federations.

- Union of Arras, a Catholic confederation of southern Netherland provinces, remained under Spanish dominion

- Union of Utrecht, Protestant northern provinces, became the Dutch Republic.

More Protestants – fewer large-scale altarpieces and religious works (Catholic churches still wanted large works).

Bosch's Garden of Earthly Delights

HIERONYMUS BOSCH, Garden of Earthly Delights, 1505-1510. Oil on wood, center panel 7’ 2 5/8” X 6’ 4 ¾”, each wing 7’ 2 5/8” X 3’ 2 ¼”. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

Link to interactive high resolution image. (Requires Flash)

HIERONYMOUS BOSCH

- Most famous Netherlandish painter

- most famous work is Garden of Earthly Delights

Lots of debate of who he was as a person

- A satirist, mocked religion, or a pornographer

- A heretic or an orthodox fanatic like Savonarola

The Garden of Earthly Delights is a large-scale triptych that seems religious but was found in the palace of Henry III of Nassau. This location suggests a secular commission for private use

Central themes of marriage, sex, and procreation. Probably commemorates a wedding such as Giovanni Arnolfini and His Bride

In the left panel

- God presents Eve to Adam in a landscape, presumably the Garden of Eden

- Odd pink fountain like structure in a body of water

- unusual animals

- Hint at an interpretation involving alchemy

- the medieval study of seemingly magical changes, especially chemical changes

- (Witchcraft also involved alchemy)

The right panel

- shows the horrors of Hell

- creatures devour people

- Others are impaled or strung on musical instruments

- A gambler is nailed to his own table

- A spidery monster embraces a girl while toads bite her

Middle

- Nude people dance

- bizarre creatures and unidentifiable objects

- Numerous fruits and birds (fertility symbols) in the scene suggest procreation

- Many of the figures are paired off as couples

- seems like an orgy

The Garden of Earthly Delights is the modern title given to a triptych painted by the Early Netherlandish master Hieronymus Bosch. It has been housed in the Museo del Prado in Madrid since 1939. Dating from between 1490 and 1510, when Bosch was about 40 or 50 years old, it is his best-known and most ambitious, complete work. It reveals the artist at the height of his powers; in no other painting does he achieve such complexity of meaning or such vivid imagery. The triptych is painted in oil on oak and is formed from a square middle panel flanked by two other oak rectangular wings that close over the center as shutters. The outer wings, when folded, show a grisaille painting of the earth during the biblical narrative of Creation. The three scenes of the inner triptych are probably (but not necessarily) intended to be read chronologically from left to right. The left panel depicts God presenting Eve to Adam, the central panel is a broad panorama of sexually engaged nude figures, fantastical animals, oversized fruit and hybrid stone formations. The right panel is a hellscape and portrays the torments of damnation.

Art historians and critics frequently interpret the painting as a didactic warning on the perils of life’s temptations. However, the intricacy of its symbolism, particularly that of the central panel, has led to a wide range of scholarly interpretations over the centuries. Twentieth-century art historians are divided as to whether the triptych‘s central panel is a moral warning or a panorama of paradise lost. American writer Peter S. Beagle describes it as an “erotic derangement that turns us all into voyeurs, a place filled with the intoxicating air of perfect liberty”.

During his lifetime, Bosch painted three large triptychs that can be read from left to right and in which each panel was essential to the meaning of the whole. Each of these three works presents distinct yet linked themes addressing history and faith. Triptychs from this period were generally intended to be read sequentially, the left and right panels often portraying Eden and the Last Judgment respectively, while the subtext was contained in the center piece. It is not known whether “The Garden” was intended as an altarpiece, but the general view is that the extreme subject matter of the inner center and right panels make it unlikely that it was intended to function in a church or monastery, but was instead commissioned by a lay patron.

The Money-Changer and His Wife

QUINTEN MASSYS, Money-Changer and His Wife, 1514. Oil on wood, 2’ 3 3/4” x 2’ 2 3/8”. Louvre, Paris.

This artist’s name is also spelled Metsys. The painting is also titled the Moneylender and His Wife.

Metsys in Antwerp, the economic capital of Europe

Quentin Metsys was born in Louvain in 1466. He later settled in Antwerp, where he is mentioned in 1491 as a master, and where he died in 1530. At that time, the town was a major trading center and rapidly became the principal city for commerce between northern and southern Europe. Portuguese and Spanish merchants and powerful Italian bankers visited Antwerp for trade, making the bustling city the economic capital of Europe. One consequence of the presence of merchants from all over Europe using a variety of currencies was that large numbers of moneylenders and money changers set up shop in the towns where most of the foreigners traded, such as Bruges and, above all, Antwerp. This famous painting by Metsys, once owned by Rubens, is set in one of these cities.

The moneylender and his wife

The two subjects are depicted half-length, seated behind a table. The scene is tightly framed, making them the focus of attention. They are in perfect symmetry. The man is busy weighing the pearls, jewels, and pieces of gold on the table in front of him. This is distracting his wife from the book she is reading-a work of devotion, as the illustration of the Virgin and Child shows. The mirror placed in the foreground-a common device in Flemish painting, allowing the artist to create a link with the space beyond the framed scene-reflects a figure standing in front of a window. On the right, a door stands ajar, revealing a youth talking to an old man. The artist has produced an archaic rendering of the volumes and colors, opposing red and green, for instance. This fact, as well as the minute level of detail of the objects depicted, has led some art historians to speculate that this might be an imitation of a lost work by Jan van Eyck.

A painting with a moral

The second half of the fifteenth century in northern Europe saw an expansion of genre painting-landscapes, portraits, and scenes of daily life, which artists depicted with moralizing overtones as a way of condemning human vices and reminding viewers of the frailty of human existence. These are precisely the aspects that Metsys often considered one of the founders of the genre-highlights in this work. The shiny gold, pearls (a symbol of lust), and jewelry have distracted the wife from her spiritual duty, reading a work of devotion. The objects in the background have been carefully chosen to strengthen the work’s moral message. The snuffed-out candle and the fruit on the shelf-an allusion to original sin and a reminder that we are all doomed to return to dust-are symbols of death. The carafe of water and the rosary hanging from the shelf symbolize the purity of the Virgin. Finally, the small wooden box represents a place where faith has retired. Other artists, most notably Marinus van Reymerswaele, painted many works on a similar theme.

Aertsen's Butcher's Stall

PIETER AERTSEN, Butcher’s Stall, 1551. Oil on wood, 4’ 3/8” x 6’ 5 3/4”. Uppsala University Art Collection, Uppsala.

Butcher’s Stall by PIETER AERTSEN

Worked in Antwerp for more than three decades

This painting appears to be a descriptive genre scene (one from everyday life)

- On display is a collection of meat products

- hog, chickens, sausages, a stuffed intestine, pig’s feet

- Meat pies, a cow’s head, a hog’s head, and hanging entrails

- fish, pretzels, cheese, and butter

Strategically placed religious images in his painting

- In the background, Joseph leads a donkey carrying Mary and Christ

- The Holy Family stops to offer money to a beggar and his son

- The people behind the Holy Family are on their way to church

Crossed fishes on the platter and the pretzels and wine in the rafters on the upper left

- All refer to “spiritual food” (pretzels often served as bread during Lent)

Allusions to salvation through Christ by contrasting them to their opposite

- A life of gluttony, lust, and sloth

He represented this degeneracy with the oyster and mussel shells

- (which Netherlanders believed possessed aphrodisiacal properties)

- Scattered on the ground on the painting’s right side

In the 16th and 17th centuries it was quite common for theologians to see a slaughtered animal as symbolizing the death of a believer. Allusions to the ‘weak flesh’ (cf. Matthew 16:41) may well have been associated with Aertsen’s Butcher’s Stall where – like on his fruit and vegetable stalls – a seemingly infinite abundance of meat has been spread out.

In the foreground tables, pots, plates, a barrel, some wickerwork chairs and baskets serve as supports and containers for huge hunks of meat, pig’s trotters, soups, chains of sausages hanging down and freshly slaughtered poultry. In the background there is an open, shingle-roofed studded stable with a pole from which further pieces of meat are suspended, including a pig’s head, a twisted sausage and some lard. Through the stable we can see a garden scene. On the right, in the middle ground, a farmer is filling a large jug, and behind him we can see a slaughtered and gutted pig, a motif which Beuckelaer also used as an independent motif, as did Rembrandt later (where the animal is a slaughtered ox).

Pieter Aertsen is remembered today mainly as a pioneer of still lifes, but he seems to have first painted such pictures as a sideline, until he saw many of his altarpieces destroyed by iconoclasts. This painting, done a few years before he moved from Antwerp to Amsterdam, seems at first glance to be an essentially secular picture. The tiny, distant figures are almost blotted out by the avalanche of edibles in the foreground. We see little interest here in selection or formal arrangement. The objects, piled in heaps or strung from poles, are meant to overwhelm us with their sensuous reality (the panel is nearly life-size). Here the still life so dominates the picture that it seems independent of the religious subject. The latter, however, is not merely a pretext to justify the painting; it must be integral to the meaning of the scene. In the background to the left we see the Virgin on the Flight into Egypt dispensing charity to the faithful lined up for church, while to the right is the prodigal son in a tavern. The Northern Mannerists often relegated subject matter to a minor position within their compositions.

Pieter Aertsen was one of the first artists to paint “inverted still lifes,” works in which the still-life elements are placed prominently in the foreground, while the narrative elements are relegated to the background. The Butcher’s Stall is Aertsen’s masterpiece in this genre. A feast for the mind as well as the eyes, this remarkably executed painting abounds with rich symbolism. The juxtaposition of the precisely rendered meats and other foods with the Holy Family in the background symbolically links food for the body with the spiritual “bread of life”- food for the soul, represented by the Christ child and the bread, offered by Mary to the poor family. In presenting a visual metaphor that encourages the viewer to consider his spiritual life, this work also anticipates the symbolic religious meanings present in seventeenth-century Dutch vanitas still lifes. Aertsen’s Meat Stall was clearly a famous work in its own day, judging from the number of contemporary versions that exist. In both style and subject matter, the Butcher’s Stall is the direct antecedent of the impressive Market Scene on a Quay by Frans Snyders.

This “inverted” perspective was a favorite device of Aertsen’s younger contemporary, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, who treated it with mocking intent in his landscapes. Aertsen belonged to the same ironic tradition, reaching back to the Gothic era, whose greatest representative was the humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam. The Butcher’s Stall may be an elaborate satire on the gluttony of peasants, a favorite subject of Bruegel. Not until around 1600 was this vision replaced as part of a larger change in world view. Only then did it no longer prove necessary to include religious or historical scenes in still lifes and landscapes.

Bruegel the Elder

Netherlandish Proverbs by PIETER BRUEGEL THE ELDER

Greatest Netherlandish painter of the mid-16th century

- relationship between humans and nature

Traveled to Italy

- Spent almost two years, venturing as far south as Sicily

Netherlandish Proverbs

- Netherlandish village populated by a wide range of people

- (nobility, peasants, and clerics)

- Bird’s-eye view

- lots of activity

- more than a hundred proverbs in this one painting

The proverbs depicted include

- On the far left, a man in blue gnawing on a pillar (hypocrisy)

- To his right, a man “beats his head against a wall” (an ambitious idiot)

- On the roof a man “shoots one arrow after the other, but hits nothing” (shortsighted)

- In the far distance, the “blind lead the blind”

PIETER BRUEGEL THE ELDER, Fall of Icarus, ca. 1555–1556. Oil on wood transferred to canvas, 2’ 5” X 3’ 8 1/8”. Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels.

PIETER BRUEGEL THE ELDER, Hunters in the Snow, 1565. Oil on wood, approx. 3’ 10 1/8” x 5’ 3 3/4”. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

Hunters in the Snow

- One of a series of six paintings (some scholars think there were originally 12

- Illustrating seasonal changes in the year

Hunters refers back to older traditions of depicting seasons and peasants in Books of Hours

- Shows human figures and landscape in winter cold

- Very cold winter of 1565, when Bruegel produced the painting

The hunters return with their dogs

- Women build fires, skaters on the frozen pond

Bruegel rendered the landscape in an optically accurate manner

- It develops smoothly from foreground to background

- Draws the viewer diagonally into its depths

Art in Spain in the 16th Century

SPAIN

- Spain’s ascent to power in Europe began in the mid-15th century

- Marriage of Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon in 1469

By the end of the 16th century, Spain had emerged as the dominant European power

- Spanish Empire controlled a territory greater in extent than any ever known

Acquired many of its New World colonies through aggressive overseas exploration

Notable conquistadors sailing under the Spanish flag

- Christopher Columbus

- Vasco Nuñez de Balboa

- Ferdinand Magellan

- Hernán Cortés

- Francisco Pizarro

- Habsburg Empire supported the most powerful military force in Europe

- Spain defended and then promoted the interests of the Catholic Church

- Philip II earned the title “Most Catholic King”

Spain’s crusading spirit, nourished by centuries of war with Islam, engaged body and soul in forming the most Catholic civilization of Europe and the Americas. In the 16th century, for good or for ill, Spain left the mark of Spanish power, religion, language, and culture on two hemispheres.

El Greco

EL GRECO

Mannerism – multiple focal points.

El Greco’s dramatic and expressionistic style was met with puzzlement by his contemporaries but found appreciation in the 20th century. El Greco is regarded as a precursor of both Expressionism and Cubism.

Doménikos Theotokópoulos (El Greco)

- Born on Crete but emigrated to Italy as a young man

- Learned from Byzantine frescoes and mosaics

- Went to Venice, where he worked in Titian’s studio

- Went to Rome where he experience Mannerism

- 1577 – left for Spain to spend the rest of his life in Toledo

El Greco's The Burial of Count Orgaz

EL GRECO, The Burial of Count Orgaz, 1586. Oil on canvas, 16’ x 12’. Santo Tomé, Toledo.

The upper half of the image is very abstract for it’s time, with elongated forms and active brushwork, while the bottom half is more in keeping with mannerist traditions. Intense emotionalism of his paintings and reliance on and mastery of color. El Greco’s style captured the intensity of Spanish Catholicism.

Burial of Count Orgaz

- Painted in 1586 for the church of Santo Tomé in Toledo

- Based the painting on the legend of the count of Orgaz,

- Buried in the church by Saints Stephen and Augustine

- (descended from Heaven to lower the count’s body in the tome)

Represented the earthly realm with realism.

- Depicted the heavenly with elongated figures, draperies, and a swirling cloud

Below, the two saints lower the count’s body.

El Greco, The Burial of Count Orgaz 1586 Oil on canvas, 480 x 360 cm, Santo Tome, Toledo

Multiple focal points is evident in this painting.

The upper half of the image is very abstract for it’s time

- elongated forms

- active brushwork

Bottom half is more mannerist.

- El Greco’s best known work

- Illustrates a popular local legend.

An exceptionally large painting

- Divided into two zones:

- heavenly above

- terrestrial below.

El Greco is his nickname meaning The Greek

- 1541 – 1614

- was a painter, sculptor, and architect of the Spanish Renaissance.

- Usually signed his paintings in Greek letters with his full name, Doménicos Theotokópoulos

- Born in Crete

- At 26 he traveled to Venice to study

- In 1570 he moved to Rome, where he opened a workshop and completed a series of works.

- In 1577 he immigrated to Toledo, Spain, where he lived and worked until his death.

- In Toledo, El Greco received several major commissions and produced his best known paintings.

El Greco’s dramatic and expressionistic style

- Met with puzzlement by his contemporaries

- Found appreciation in the 20th century.

El Greco is seen as a precursor to both Expressionism and Cubism

- Belongs to no conventional school.

- Best known for elongated figures and fantastic and unusual colors

The Burial of the Count of Orgaz is a painting by El Greco, a painter, sculptor, and architect of the Spanish Renaissance. Widely considered among his finest works, it illustrates a popular local legend of his time. An exceptionally large painting, it is very clearly divided into two sections, heavenly above and terrestrial below, but it gives little impression of duality. The upper and lower sections are brought together compositionally.The theme of the painting is inspired from a legend of the beginning of the 14th century. In 1312, a certain Don Gonzalo Ruíz, native of Toledo, and Señor of the town of Orgaz, died (his family later received the title of Count, by which he is generally and posthumously known). The Count of Orgaz was a pious man who, among other charitable acts, left a sum of money for the enlargement and adornment of the church of Santo Tomé (El Greco’s parish church). He was also a philanthropist and a right-thinking Knight. According to the legend, at the time he was buried, Saint Stephen and Saint Augustine descended in person from the heavens and buried him by their own hands in front of the dazzled eyes of those present.

The painting was commissioned by Andrés Núñez, the parish priest of Santo Tomé, for the side-chapel of the Virgin of the church of Santo Tomé, and was executed by El Greco between 1586–1588. Núñez, who had initiated a project to refurbish the Count’s burial chapel, is portrayed in the painting reading.

Already in 1588, people were flocking to Orgaz to see the painting. This immediate popular reception depended, however, on the lifelike portrayal of the notable men of Toledo of the time.It was the custom for the eminent and noble men of the town to assist the burial of the noble-born, and it was stipulated in the contract that the scene should be represented in this manner.

El Greco would pay homage to the aristocracy of the spirit, the clergy, the jurists, the poets and the scholars, who honored him and his art with their esteem, by immortalizing them in the painting. The Burial of the Count of Orgaz has been admired not only for its art, but also because it was a gallery of portraits of the most eminent social figures of that time in Toledo. Indeed, this painting is sufficient to rank El Greco among the few great portrait painters.

The painting is very clearly divided into two zones; above, heaven is evoked by swirling icy clouds, semiabstract in their shape, and the saints are tall and phantomlike; below, all is normal in the scale and proportions of the figures. The upper and lower zones are brought together compositionally (e.g., by the standing figures, by their varied participation in the earthly and heavenly event, by the torches, cross etc.).

The scene of the miracle is depicted in the lower part of the composition, in the terrestrial section. In the upper part, the heavenly one, the clouds have parted to receive this just man in Paradise. Christ clad in white and in glory, is the crowning point of the triangle formed by the figures of the Madonna and Saint John the Baptist in the traditional orthodoxcomposition of the Deesis. These three central figures of heavenly glory are surrounded by apostles, martyrs, Biblical kings and the just (among whom was Philip II of Spain, though he was still alive.

Saints Augustine and Stephen, in golden and red vestments respectively, bend reverently over the body of the count, who is clad in magnificent armour that reflects the yellow and reds of the other figures. The young boy at the left is El Greco’s son, Jorge Manuel; on a handkerchief in his pocket is inscribed the artist’s signature and the date 1578, the year of the boy’s birth. The artist himself can be recognised directly above the raised hand of one of the mourners immediately above the head of Saint Stephen. The men in contemporary 16th-century dress who attend the funeral are unmistakably prominent members of Toledan society.

The painting has a chromatic harmony that is incredibly rich, expressive and radiant. On the black mourning garments of the nobles are projected the gold-embroidered vestments, thus creating an intense ceremonial character. In the heavenly space there is a predominance of transparent harmonies of iridescence and ivoried greys, which harmonize with the gilded ochres, while in the maforium of Madonna deep blue is closely combined with bright red. The rhetoric of the expressions, the glances and the gestural translation make the scene very moving.

The Burial of the Count of Orgaz is regarded as the first completely personal work by the artist. There are no longer any references to Roman or Venetian formulas or motifs. He has succeeded in eliminating any description of space. There is no ground, no horizon, no sky and no perspective. Accordingly, there is no conflict, and a convincing expression of a supernatural space is achieved. According toHarold Wethey, the supernatural vision of Gloria (“Heaven”) above and the impressive array of portraits represent all aspects of this extraordinary genius’s art. Wethey also asserts that “El Greco’s Mannerist method of composition is nowhere more clearly expressed than here, where all of the action takes place in the frontal plane”.

The composition of the painting has been closely related to the Byzantine iconography of the Assumption of the Virgin. The examples that have been used to support this point of view have a close relationship with the icon of the Dormition by El Greco that was discovered in 1983 in the church of the same name in Syros. Marina Lambraki-Plaka believes that such a connection exists. Robert Byron, according to whom the iconographic type of the Dormition was the compositional model for The Burial of the Count of Orgaz, asserts that El Greco as a genuine Byzantine painter worked throughout his life with a repertoire of components and motifs at will, depending on the narrative and expressive requirements of the art. Wethey rejects as “unconvincing” the view that the composition of the Burial is derived from the Dormition, “since the work is more immediately related to Italian Renaissance prototypes”. In connection with its negation of spatial depth by compressing figures into the foreground, the early Florentine Mannerists—Rosso Fiorentino, Pontormo and Parmigianino—are mentioned, as well two paintings by Tintoretto: the Crucifixion and the Resurrection of Lazarus, the latter because of the horizontal row of spectators behind the miracle. The elliptical grouping of the two saints, as they lower the dead body, is said to be closer to Titian’s early Entombment than to any other work.

According to Lambraki-Plaka, The Burial of the Count of Orgaz is a landmark in the artist’s career. “This is where El Greco sets before us, in a highly compressed form the wisdom he has brought to his art, his knowledge, his expertise, his composite imagination and his expressive power. It is the living encyclopedia of his art without ceasing to be a masterpiece with organic continuity and entelechy”.

Sources

“Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.” Albrecht Dürer: Adam and Eve (19.73.1). N.p., n.d. Web. 01 Jan. 2013. <http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/19.73.1>.

“The Isenheim Altar.” The Isenheim Altar. N.p., n.d. Web. 01 Jan. 2013. <http://www.artbible.info/art/isenheim-altar.html>.

“Hans Baldung, Called ‘Grien’,Witches’Sabbath, a Woodcut.” British Museum. N.p., n.d. Web. 02 Jan. 2013. <http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/pd/h/hans_baldung,_called_grien,_wi.aspx>.

“Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.” Albrecht Durer (1471 – 1528). N.p., n.d. Web. 02 Jan. 2013. <http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/durr/hd_durr.htm>.

“Engraving Image Map.” Knight Death and the Devil by Albrecht Dürer. N.p., n.d. Web. 02 Jan. 2013. <http://www.spencerart.ku.edu/collection/print/maps/ritter.shtml>.

“The Reformation.” History.com. A&E Television Networks, n.d. Web. 02 Jan. 2013. <http://www.history.com/topics/reformation>.

Scribner, R. W. For the Sake of Simple Folk: Popular Propaganda for the German Reformation. N.p.: Cambridge UP, 1981. Print.

“Work The Moneylender and His Wife.” The Moneylender and His Wife. N.p., n.d. Web. 02 Jan. 2013. <http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/moneylender-and-his-wife>.

“Aertsen, Pieter.” WebMuseum: : Butcher’s Stall with the Flight into Egypt. N.p., n.d. Web. 02 Jan. 2013. <http://www.ibiblio.org/wm/paint/auth/aertsen/butchers-stall/>.